Abandoned in October 2020 according to my Mac. Pandemic tax.

Martin

My family moved from Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada to Martinsville, Virginia, United States in December 1996. If you asked me then I was "six-and-a-half," just old enough to remember before and after. I was held out of school until January 1997, and it was then I first encountered Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Despite his birthday being 15 January, King's commemoration is a moving target. This happens because the holiday's initial campaign was sustained by labor unions. King was incredibly supportive of collectivism and unionisation. His death happened in Memphis, Tennessee for that reason. He was there to support black sanitation workers on strike against the city due to low wages and unfair treatment compared to their white counterparts.

On the evening of 4 April 1968, King was shot by an assassin's bullet on the balcony of his Lorraine Motel room in Memphis. He was rushed to hospital, underwent life-saving surgery, but the damage was too great. The civil rights leader died aged 39. Four days later, as parts of Washington, D.C., Chicago, Baltimore, Detroit, and other cities around the United States were smouldering due to rebellions triggered by the assassination, Michigan Representative John Conyers (a founding member of the Black Congressional Congress), and Massachusetts Senator Edward Brooke, introduced the first congressional bill to recognize King.

In the years following his death, many black workers around the country took 15 January off work. Were it not for the significant power of trade unions, many of those workers would have been fired, and the campaign to establish a national holiday would have perhaps faded. In labor disputes for over a decade after 1968, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, the Distributive Workers of America, the United Autoworkers, and other unions campaigned to pass Brooke and Conyers’ bill, wanting it to be a paid holiday, in honor of the work King was attempting to accomplish before his death.

The 1970s were an important decade for unionisation. Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it was just about legal to discriminate against anyone for any reason. While in theory there were already laws on the books to prevent such behaviour, they were not always followed, nor enforced. Title XII of the 1964 Act states: "It shall be unlawful employment practice for an employer to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual...because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin." The same standard applied to employment agencies, and labor organisations. Unsurprisingly, that wasn't enough. Eight years later Congress passed the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 which amended Title XII, allowing the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to take action against individuals, employers, and labor unions who violated the unchanged provisions established in 1964, and the revisions established in 1972.

This meant in a sentence: Black people had an easier path gaining employment (at companies established by white people) and entering trade unions (established by white workers) in the 1970s than at any point previously. Having more representation in labor unions, black workers were now able to enter their demands into the many labour clashes the 1970s had to offer, and one of them was a paid holiday honouring the life and legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Jimmy Carter was elected President of the United States in 1976. Carter endorsed the bill for King's holiday in 1979 acknowledging the influence labour unions brought to his election three years previous. The bill ultimately failed by three votes. Some in Congress weren't willing to give a day off with pay to the nation, others were openly racist and didn't want to give a black man a federal holiday. There was a third category who fell into both camps. After one term, Carter left the Presidency in 1980; the country voted against the Georgia-born Democrat in favour of Republican and former California governor Ronald Reagan.

The power of unions began decreasing in the 1980s, in no small part because of Reagan, but the general public was in support of the holiday. Stevie Wonder dedicated his version of "Happy Birthday" to King in 1980, adding fuel to the fire. Conyers and Brooke's attempt failed, but in August 1983, representative from Indiana Katie Hall sponsored legislation to make King's birthday a federal holiday with pay. This time, the bill passed the House of Representatives 338–90, passed the Senate 78–22 (both veto-proof margins), and in November 1983 Reagan signed the bill into law, with the holiday scheduled to go into effect January 1986. The Reagan administration enacting MLK Day is rather peculiar, but when Stevie is for you, who can be against you?

Each state had its own implementation process, and the Commonwealth of Virginia decided: "You know? This Martin Luther King thing. We'll do it, but we're not gonna give him his own day. We're gonna add the man assassinated working on behalf of black people to the holiday we already have for two generals from the Confederate States of America, a secessionist regime, who fought to keep slavery." Why rests in the Civil War.

Southern states had millions of enslaved Africans working on plantations by 1860. Northern states benefited from the institution of slavery, but its economy mostly revolved around industry. The robber barons many are familiar with (Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, J. P. Morgan) either owned an industry or were preparing to own one. The Southern economy was almost exclusively agricultural, relying on slave labor to farm cash crops like tobacco and cotton. As the horrors of chattel slavery were revealed by formerly enslaved people, anti-slavery sentiment rose. Ending slavery was unfathomable for the South, as paying people (when classed as people) to work would drastically reduce the plantation economy.

Approaching the 1860 presidential election the country was a powder keg waiting to explode. Congress passed the Kansas-Missouri Act in 1854, essentially voiding the Missouri Compromise which was meant to keep a balance of free states and slave states in the Union. The Act tilted the country, making many in the North (who were uncomfortable with slavery spreading as free labour made Southern conglomerates competitive with their industries) intent on making the South face consequences. Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin sold over one million copies worldwide by 1855. The book was a touchstone for the abolitionist movement, as its strong moral indictment of slavery resonated with many of its Christian readers. The Dread Scott decision was given by the United States Supreme Court in 1857. It ruled that black people were not citizens, and had no right to due process of law. Their decision stated Congress had no authority to ban slavery in any state. It reinforced the notion black people were merely property, which amplified the growing tension.

White abolitionist John Brown led an assault in Harpers Ferry, Virginia on a United States military arsenal in October 1959. He was attempting to collect weapons for an armed slave revolt. His assault failed, he was captured and hung along with several of his cohort, but his group’s actions were seen as brave by many in the North who increasingly believed the gun was the only means by which to end slavery. Southerners saw Brown's Harpers Ferry raid as a precursor for war, as it displayed there were white people willing to die to end slavery in the United States.

The final straw was the 1860 presidential election. The two main contenders for the presidency were Southern Democrat candidate John C. Breckinridge and Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln. Breckinridge signalled the continuation of slavery; Lincoln signified its halt. Lincoln won rather handsomely as the Republican Party's anti-slavery stance won them the decisive Northern majority. Breckinridge was the last hope of keeping the Union intact, and his defeat triggered seven states leaving the United States. Lincoln was inaugurated in March 1861, and one month later at Fort Sumter in South Carolina, the American Civil War began. Four more states left the Union, including Virginia.

The American Civil War was long and costly. Over the five years of conflict, it's estimated over 600,000 Americans were killed, and over 400,000 were wounded. The Confederacy was at a disadvantage. They had less money, fewer soldiers, and poor international standing. Their biggest advantage was perhaps psychological. Losing the war meant slavery's end, and slavery's end meant the South would no longer be economically viable. As they viewed it, their cause was survival, but when the conflict became less about cause and more about attrition, the Union's superior infrastructure began to crush the Confederacy.

As the war came to its conclusion, Lincoln had to balance the South's reintegration with the war's central issues, chief among them: What do we do with the millions of Africans on Southern plantations? His first move was the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. This freed enslaved people living within the boundaries of the Confederacy, but not those enslaved people living in the Union, nor those within border states. Understanding states within the Union had the freedom to decide for themselves, Lincoln presumed the proclamation wasn't strong enough and wanted an amendment made to the Constitution permanently outlawing slavery in the Union. Before the 1864 presidential election, the Senate passed the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The amendment abolished slavery and indentured servitude, except as punishment for a crime.

Lincoln was re-elected and took his second oath in March 1865. The war ended in April and things seemed positive for the incumbent. He had maintained the union, and was on pace to end slavery with a constitutional amendment, but on 14 April (a week after the war concluded) Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathiser John Wilkes Booth. Attempting to avoid further conflict, Lincoln's presidential replacement Andrew Johnson had a decision to make: If the purpose of the war was maintaining union, how forceful should the North be with Confederate states? He decided against a heavy-handed approach and opted for kid's gloves. The only real "punishment" Confederate states received was ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment. Once doing so, Johnson was largely happy to let them do as they pleased. He vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, and was against the Fourteenth Amendment which offered newly freed Africans "equal protection under the law.”

With this backdrop, the South began the process of collecting their thoughts. Asking themselves: What happened during the war? Who is to blame? Who are our heroes? In answering those questions, the Lost Cause of the Confederacy was birthed. Lost Cause ideology suggests despite its outcome, the Civil War was a justified and righteous cause. It posits the North's victory was a forgone conclusion, but the Confederacy was brave to fight for their values (those being chattel slavery), even if the odds were stacked against them. It places the blame at the feet of the North, suggesting the South were merely playing defense, calling it the "War of Northern Aggression." This ideology was allowed to fester in part because of the approach enacted by the federal government immediately following the war. Johnson's tepidness and indifference to African people essentially gave "get out of jail free" cards to Confederate soldiers and politicians.

A central figure of Lost Cause theology is General of the Northern Army of Virginia (the South's principal fighting force during the conflict) Robert E. Lee. The son of former Virginia governor and United States Army general Henry Lee, Robert followed his father into the Union Army. A proud Virginian, Lee left the United States Army to lead the Confederate States of America in armed conflict. Lost Cause mythology built Lee as the hero of heroes, so when the war began fading into history, Lee's mythology increased. In 1889, nearly twenty years after his death, Virginia dedicated a holiday to him, observing his 19 January birthday. Lee’s understudy and fellow Virginian general Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson was also included in Lost Cause lore. His nickname came from his brigade "standing like a stone wall" in the face of a Northern assault in 1861. He died during the war, a combination of friendly fire and pneumonia, but he had legendary status. In 1904, Virginia transformed Robert E. Lee Day into Lee-Jackson Day, as Jackson's 21 January birthday conveniently fit the calendar. For almost 80 years the state recognised Lee and Jackson on the third week of January, so in 1983 when President Reagan signed MLK Day into law for the third Monday every January, Virginia thought to themselves: "Just add King." They created Lee-Jackson-King Day in 1986; King's inclusion making it a paid holiday.

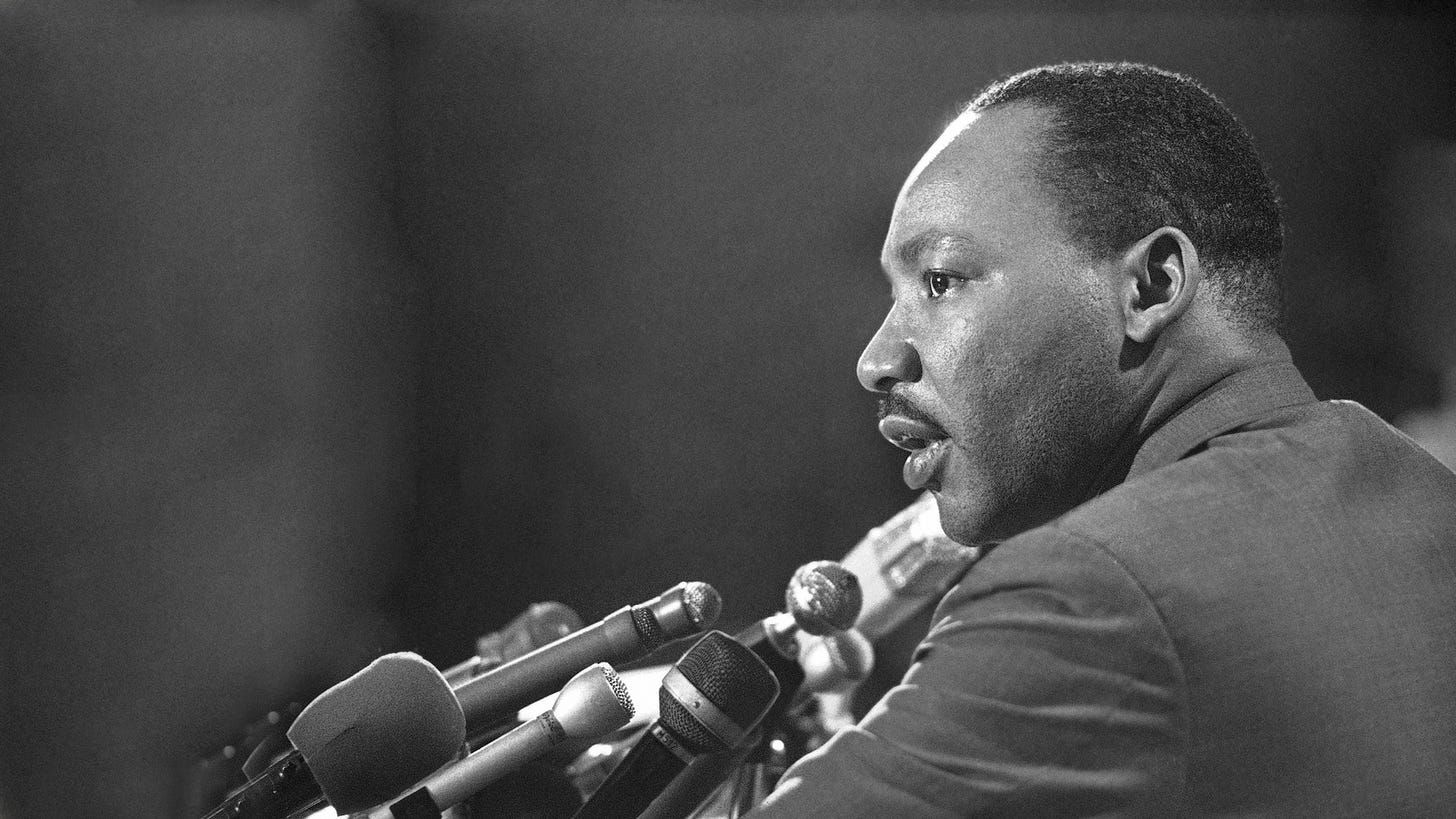

What you might be wondering is: From 1986 through 2000, what were kids in Virginia's public schools taught after they returned from winter vacation? As during that time, I began attending public school in Virginia, it so happens I can tell you exactly what was taughtt. During the 1999/2000 academic year I attended Rich Acres Elementary School, and in my fourth-grade classroom was where I concretely remember being taught lesson plans surrounding Lee-Jackson-King Day. Our main teacher would leave the classroom and another would arrive to teach history and geography. There is a packet of worksheets I can vividly recall. It had pictures of Lee on his famous horse Traveller, "Stonewall" Jackson with a sword standing beside a brick wall, and King behind a podium during the 1963 March on Washington. Our teacher told us King advocated for the rights of everyone, but there he was in the same packet of pictures with men she told us fought to keep slavery. Being "nine-and-a-half" I wasn't capable of properly analysing it, but the contradiction didn't escape me. I clearly wasn't alone in this confusion, as 2000 was the last year the three men were celebrated jointly in Virginia. In 2001 Lee-Jackson-King Day was broken in two: Lee-Jackson Day celebrated on Friday, MLK Day celebrated on Monday. One might assume their official separation would end our combined worksheets, but no, the trio continued being taught together. Virginia canceling the commemoration of their Confederate heroes wouldn't happen for another 20 years.

For seven years I was schooled in Virginia. The summer of 2003 saw my family move once more, this time to North Carolina. Though part of the Confederacy (and having Confederate memorabilia guarding what feels like every courthouse and university campus), North Carolina did not have a Lee or Jackson to honour in the way Virginia felt so compelled; so eighth grade at A. Laurin Welborn Middle School in High Point, North Carolina was the first time I enjoyed MLK Day without Robert E. Lee and "Stonewall" Jackson's company.

In Virginia it went something like: "Martin Luther King fought for civil rights. He was peaceful. He wanted everyone to get along. Then he died." Without the complication of Confederate generals, and with the benefit of age, North Carolina was where my focus turned completely to King. When I first encountered him, he wasn't alone, he was always with two white guys I didn't particularly care for. Meeting him by himself, King's message became something I wanted to explore beyond the Messianic level of: "He died for us."

The American civil rights movement began the moment the country started. Taking inspiration from English philosopher and Enlightenment thinker John Locke, Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." Enslaved Africans in 1776 heard Jefferson’s pen. Eleven years later at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, they learned the same United States thousands of Africans had fought for in the American Revolution were considered three-fifths of a human being. "If all men are created equal, where are the other two-fifths?" This inherent contradiction is the foundation upon which almost every problem involving black people in the United States has been built. Enslaved Africans fought for their humanity the second they entered the bowels of European slave ships. It explains Gabriel Prosser. It explains Denmark Vesey. It explains Nat Turner. It explains the Civil War. It explains all manner of armed and peaceful protests waged on American soil. The civil rights movement did not start in the twentieth century; the line drawn linking slave rebellions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to an Atlanta-born minister in 1929 is arrow straight.

In 1944, 15-year-old King passed Morehouse University's entrance exam. Four years later, he had a bachelor's in sociology from the historically black institution, and was pastoring at Ebenezer Baptist Church as an ordained minister under his father. King earned his Bachelor of Divinity from Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania in 1951; the same year he began graduate studies at Boston University's School of Theology, where he met Coretta Scott who was studying at the New England Conservatory of Music. By 1955, King's life seemed set. The 26-year-old was married, had his doctorate, and was lead pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, but settling into this existence was not his complete calling.

King happened upon an ideal time for activism. A decade before 1955, World War II was coming to its conclusion. The Allied Powers freed Rome and liberated Paris in 1944. The next year Berlin was sacked by the Soviet Union, and American President Harry S. Truman allowed military personnel to drop two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. The fighting ended, and American soldiers returned home. Over 125,000 black people participated abroad in the war effort. Putting their lives on the line to defeat Adolph Hitler and the Axis Powers was not enough to be considered a first-class citizen in the United States. Black Americans in greater number began building upon the legacy of what came before them and demanded their supposed "unalienable rights," as Jefferson wrote almost 200 years prior, of "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

It might have been excusable for King to settle into his life as a Baptist minister. Why make a name for yourself? Why become a target for the United States government and white racists (the distinction is unnecessary) to vent their hate? Why not wait until you're older? All fair questions to a 26-year-old, but for someone educated in the art of communication, and seeing an engine so well-primed after World War II, King was willing to step out and incur risk.

Emmett Till was visiting family near Money, Mississippi in August 1955. The 14-year-old from Chicago had an innocent encounter with 21-year-old white woman Carolyn Bryant at a local grocery store. Days after, Bryant's husband and his brother arrived at Till's uncle's house with weapons. They kidnapped the teenager, tortured him, shot him in the head, and discarded his body into the Tallahatchie River. Till was found three days later. His mother Mamie Till, wanting attention brought to the murder, bore the weight of having her son's body lie in an open-casket for the world to see, even allowing Jet magazine to take pictures. Till's disfigured face sent shockwaves throughout the country, particularly in black America. The images served to galvanise an already frustrated community, and in September 1955 when Ray Bryant and J. W. Milam were acquitted of the murder by an all-white jury of their peers, the country reached yet another boiling point.

King hosted a rally bringing attention to Till's case and others at his church in Montgomery. One attendee was Rosa Parks. A secretary for the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) chapter, Parks was arrested days later by Montgomery police on 1 December 1955 after refusing a bus driver's order to move for a white man. The buses in Montgomery were not run by the city, they were private businesses, but segregation was enforced by police. Parks was not the first black person arrested for refusing to give up their seat on a Montgomery bus. Claudette Colvin was arrested nine months earlier for the same reason, but community leaders thought she wasn't respectable enough to sustain a movement because she was 15 and pregnant. Mary Louise Smith was also arrested in 1955, but her case didn’t make headlines as the arrest was kept under wraps. Parks was seen as an ideal candidate due to her age and employment at the NAACP.

The moment Parks' case was made public, black people started boycotting buses almost immediately, as work to correct the inequities in Montgomery's busing system was not new. The Women's Political Council (WPC) founded in 1946 had long demanded change, and so to sustain the movement, four days after Parks' arrest, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was created. King was elected MIA chairman, and as such became the leading voice of the boycott. Local organizations created a list of demands for Alabama's capital, which included courteous service, the employment of black drivers, and first-come-first-serve seating. The city denied those demands, and for the next 12 months black people (who comprised 75 percent of the riders) crippled Montgomery's busing system.

Organizations like the WPC and MIA created carpools so black residents of Montgomery could travel across the city. This was not without consequence. Groups of white racists would harass and attack carpoolers and those walking by foot. On 30 January 1956, two months into the boycott, King's home was firebombed with Coretta and his firstborn of three months inside. The boycott made the city turn to extreme methods to end the resistance. They banned the use of carpools and began arresting drivers, as well as leaders — King himself was charged and jailed. This ultimately proved unwise, as in Montgomery's eagerness to neutralise the boycott they increased its awareness and strengthened the people's resolve.

Progressing alongside the bus boycott was a civil lawsuit created by black leaders in Montgomery. It claimed the busing system was unconstitutional and appealed to the Fourteenth Amendment's clause for "equal protection under the law." MIA attorney Fred Gray filed the suit in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama, representing Colvin, Smith, Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, and Jeanetta Reese (who later withdrew), all women subjected to discrimination on Montgomery's buses. Gray was joined by NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyers Robert L. Carter and Thurgood Marshall. The District Court ruled in June 1956 the discrimination on Montgomery's buses was unconstitutional. The state of Alabama and the city of Montgomery appealed to the Supreme Court, but the original decision was upheld in November 1956. One month later the boycott ended; buses in Montgomery were theoretically desegregated. It was a massive victory for the movement, and the boycott's effectiveness thrust King into the national spotlight.

In 1957 King was named president of the newly formed Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), found himself on the cover of Time magazine, and delivered his first address to the nation at the Lincoln Memorial entitled "Give Us the Ballot." The next year he was stabbed in Harlem, New York during a book signing event, narrowly escaping with his life. King moved back to his hometown of Atlanta in 1960 and joined a failed desegregation movement in Albany, Georgia — twice being jailed in 1961 and 1962.

Experiencing defeat on the national stage, King was made to rethink his approach. He saw Birmingham as an ideal battleground for SCLC's next campaign and began directing his efforts to Alabama's largest city in 1963. The Birmingham campaign was a resounding success. King's strategy involved five key pillars. The first was an economic boycott of the city's downtown businesses. The second was knowing Birmingham's Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene "Bull" Connor was a staunch segregationist and would use any means to squash protests. The third was allowing school children to participate in the protests. The fourth was understanding news media would be in attendance. The fifth, and most clever pillar, was predicting the combustible combination of those four would trigger shock and outrage in the minds of those watching across the country, and indeed the world.

When the nonviolent protests began in April 1963, King was arrested. In was then he wrote “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which lamented the inaction of white liberals to the cause of integration and explained why nonviolent protest was the cornerstone of his philosophy. Protesting continued even with jails at full capacity. True to form, Connor allowed police to use firehoses and attack dogs on peaceful protesters — many of whom children. Photojournalists and television cameras captured the barbarity. As King predicted, seeing such inhumane treatment was difficult for those of goodwill around the world to reconcile. Connor was removed from his position in May 1963, and Birmingham was forced into taking desegregation measures. SCLC's victory catapulted King onto the international stage and helped promote the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom happening three months later in August 1963.

Esteemed civil rights figure A. Phillip Randolph planned the original March on Washington in 1941, and its threat was used to gain several initiatives from the government. But from the early 1960s, Randolph and organiser Bayard Rustin were behind the scenes planning another version of the event. The summer of 1963 combined SCLC's victory in Birmingham, the assassination of NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers, President John F. Kennedy's administration willing to take legislative action, and the 100th anniversary of Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. All of these together seemed an advantageous moment to mobilise thousands of black people into the nation's capital for a mass demonstration. Randolph and Rustin contacted SCLC, and they agreed to participate.

The march took place on 28 August 1963, organised with the participation of black and Jewish civil rights leaders, white union leaders, and various celebrities from music, film, and sports. Over 250,000 people attended the event. When the march reached its destination in front of the Lincoln Memorial a list of venerable speakers offered their thoughts on the state of America. The last speech of many was given by King. Randolph and Rustin knew the oratory skill of the 34-year-old minister, and his address was the most highly anticipated of the event.

Considering what it did to the civil rights movement, what it did for King himself, and how it's been used in subsequent decades, "I Have a Dream" is perhaps the chief speech in American history. King effortlessly weaved together the Emancipation Proclamation, the Declaration of Independence, and the United States Constitution with the Bible in his overarching demand of equality. He explained the century-long plight black people faced, placing the blame on America’s failure in living up to the promises written in its founding documents. King was insistent the time for justice (both sociologically and economically) was long overdue, and that the country would never have true peace unless the millions of black Americans living in the United States were made equal citizens. King — at the behest of legendary gospel singer Mahalia Jackson — transitioned into telling the audience about his "dream." It was not the first time he talked about it, but the previous times didn't have 250,000 people in attendance, nor millions listening on radio or watching on television. King's dream was an aspirational outcry to the highest ideals America espoused. It saw black and white people sitting together in unity as brothers and sisters. It saw his children living in a nation where their race was secondary to their character. It saw the United States as being a place of justice and equality for all people. The speech resonated deeply and is thought by many as King's magnum opus. It garnered such a response that the Federal Bureau of Investigation, who was spying on members of the civil rights movement, increased their surveillance into SCLC — viewing King as "the most dangerous Negro of the future."

The March on Washington and Kennedy's assassination three months later served as the two main catalysts for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passing. The act enforced the Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth Amendment (which made it illegal to deny someone their right vote based on their race or skin color). But as Southern states were still in the habit of disenfranchising black voters, in March 1965, five months after winning the Nobel Peace Prize, King was again in Alabama — there he helped mobilise the march from Selma to Montgomery, which demanded the 1964 Act be respected. The Selma campaign again used nonviolence, which was again responded to with state violence. On what is known as "Bloody Sunday," when attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge hundreds of peaceful protesters were beaten by Alabama state troopers. Most famously Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chairman John Lewis suffered a fractured skull after being clubbed. The images broadcasted were gut wrenching, and the campaign was ultimately successful as it helped pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965, further bolstering King's reputation as an elite civil rights campaigner.

Around here, though, is when my teachers would skip to 4 April 1968. It was almost like the last three years of King's life were inconsequential; as if his assassination was so important there wasn’t time to discuss anything else, but why skip over the last three years of someone's life if they only lived to 39? It never made sense until I read for myself, and what was found is despite all the work King accomplished from 1955 through 1965, his last three years were arguably his most important, and their exclusion from my classroom was not by accident. His tenor was changing.

After the 1965 Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles, King’s attention moved from the South to urban areas in the North and West. The legislation gained from 1955 through 1965 was primarily aimed at dismantling Jim Crow laws in southern states, it was not directed at addressing racism elsewhere. Recognising this, King moved to Chicago in January 1966 in a preemptive gambit to install nonviolent action before rebellion rose to the surface. In Illinois SCLC joined with other organizations to implement peaceful solutions. The North used (and still uses) the South’s overt racism as a shield with which to hide their own. King was made to grapple with a new dynamic. Leading demonstrations through Chicago demanding open housing, SCLC were faced with virulent racism from white people who were against integration.

The timing of King's move North was compounded by the ascension of young militant voices. In 1966 Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California, and leadership at SNCC changed hands from Lewis to Kwame Ture (then Stokely Carmichael). These developments created division, as King's dedication to nonviolence was questioned by many younger activists who increasingly favoured revolutionary black nationalism, as laid out by Marcus Garvey, Robert F. Williams, and Malcolm X.

Propelled by a radical belief in the power of love and the humanity of others, nonviolence is revolutionary in its own right, but its most important element is shame. Shame was why King wanted school students to join the demonstrations in Birmingham. He knew watching children being sprayed with pressurised water hoses and bitten by German Shepherds while peacefully marching would shame enough white Americans into a self-reflective process that resulted in tangible legislative change. As a Baptist minister King deeply believed in redemption, that even the most depraved racist could be changed if they were made to look at themselves, but Chicago was an eye-opener. When a strategy rooted in the convicting power of shame meets shameless people, it can only be but so effective.

Nonviolence was merely tactical in the minds of Carmichael, Seale, and Newton. For those who shared and inspired their thinking, if nonviolent tactics weren't effective, violence remained viable. For SCLC, nonviolent demonstration was not just tactical, it was a moral and philosophical imperative. King was eternally bound to the philosophy of nonviolence. Despite disagreements with the more militant factions of the freedom struggle, King’s main function was not as an arbiter of black morality, as is now commonplace. If violence occurs today where black people are involved, the first thing those in power do is invoke “Dr. King.” They attempt to use his nonviolent philosophy as a stick with which to beat those exhibiting frustration in anything more aggressive than a peaceful march. In reality, King’s primary function was speaking to America about its culpability in the situation faced by millions of black Americans. Using King’s words to denounce black anger while ignoring his words explaining why that anger exists is hypocrisy of the highest order.

On 14 April 1967, he gave a speech called “The Other America” at Stanford University. The first time I read and heard it was my freshman year of university. It made me angry. What annoyed me was for all the years of education I had, from Lee-Jackson-King Day, to MLK Day, even Black History Month, I was never shown the real King. I didn't know he existed, and I felt anger. In the address he expressed to the audience:

It’s a nice thing to say to people that you ought to lift yourself by your own bootstraps, but it is a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps. And the fact is that millions of Negroes, as a result of centuries of denial and neglect, have been left bootless. They find themselves impoverished aliens in this affluent society. And there is a great deal that the society can, and must do if the Negro is to gain the economic security that he needs.

Every time black people complain about systemic inequities, without fail a voice from the back of the room will shout: “Why can’t you just work harder? And why are you so angry? Martin Luther King said [insert any mollifying quote of your choosing].” Reducing King’s message to placating sound bites harms his work if one is never made to grapple with the injustices built into American society. King knew the only way to heal a sick patient is correctly diagnosing their ailment, then treating it. If a patient doesn’t know they’re sick (or refuses to admit they’re sick) the prognosis is hopeless. If you went by what we’re taught, you’d think his only remedy was love — but that’s not the complete picture. His was a three-dimensional perspective.

As laid out in “The Other America” King was committed to transformative economics, as there can be no freedom without redistribution of wealth. A misnomer exists that suggests: “Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves.” It’s not true. Lincoln did not free enslaved Africans, they were emancipated. The difference is key. Emancipation means to be released. Freedom denotes an individual having power over their future. If black people were truly “free” when slavery was abolished, the century leading to King’s arrival would have rendered his work redundant. He may have taken over his father’s church in Atlanta, and perhaps lived a relatively unknown (but longer) life if that were the case, but freedom was never on offer. Freedom is bound to self-determination, and self-determination is bound to economics. Black Americans have never enjoyed the ability to create an economic base for a sustained period, and in places where collectivism might have been created, it was burned to ash. At Stanford, King said:

In 1964 the Civil Rights Bill came into being after the Birmingham movement, which did a great deal to subpoena the conscience of a large segment of the nation to appear before the judgment seat of morality on the whole question of civil rights. After the Selma movement in 1965, we were able to get a Voting Rights Bill. And all of these things represented strides. But we must see that the struggle today is much more difficult. It's more difficult today because we are struggling now for genuine equality.

It's much easier to integrate a lunch counter than it is to guarantee a livable income and a good solid job. It's much easier to guarantee the right to vote than it is to guarantee the right to live in sanitary, decent housing conditions. It is much easier to integrate a public park than it is to make genuine, quality, integrated education a reality. And so today we are struggling for something which says we demand genuine equality.

He was clear in his assessment: without redistribution, the plight of black people — and consequently the country — would continue. By 1968 SCLC were mobilising around these ideas with their “Poor People’s Campaign.” This movement was targeted at disadvantaged and underprivileged masses around the country. King was attempting to create a diverse coalition, return to Washington D.C., and demand among other things an annual guaranteed income and low-income housing.

There were several issues with this campaign, chief among them: King was not well-liked in 1968. His economic arguments and dedication to socialist principles made him instantly adversarial, but the largest contributing factors to King's decline in popularity was his stance against the Vietnam War. That tied his heavy-handed approach to the ills of capitalism with the geopolitical reality facing the West in relation to the East. From 1965 through 1973 the United States waged war in Vietnam because (as outlined in the domino theory) they could not afford communist thought to spread throughout Asia. When President Lyndon B. Johnson sent the first American servicemen to Vietnam, anti-war sentiment existed but it was not as mainstream as when the United States ended their participation. Where anti-war sentiment enthusiastically existed from the beginning, however, was with the youth.

SNCC were the first major civil rights organisation to publicly condemn the war in 1965. Young black men were disproportionally conscripted into the United States Armed Forces, most notably legendary heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali, who was stripped of his titles in 1966 after refusing to obey his draft order. The same year James Meredith (the first black student to attend the University of Mississippi) began his March Against Fear. The march was a 220-mile walk from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi. On the second day of his march, Meredith was shot and badly wounded. Various organizations rallied around Meredith and vowed to complete his march through the state of Mississippi. SNCC and SCLC participated in the demonstration. It was that 220-mile march where Ture (then Carmichael) popularised “Black Power” in Greenwood, Mississippi, and where SNCC leaders implored King to make a public statement denouncing the war in Vietnam.

It was hypocritical for a man devoted to the principles of nonviolence and the redistribution of wealth to not boisterously condemn an expensive war which sent poor men — in particular black men — to die in Asia. And for what, American imperialism? It was a contradiction King could not escape. Ten days before his visit to Stanford, King gave a speech entitled "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence" at Riverside Church in Manhattan on 4 April 1967. Exactly one year before he was murdered, King told those gathered:

As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they ask — and rightly so — what about Vietnam? They ask if our own nation wasn't using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted.

Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of the hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent.

“Beyond Vietnam” is an impeccable encapsulation of King’s ideology. It hit the tried and true notes of America living up to the standard she set for herself, and touched the ambitious vision of unity — but at the same time didn’t shy from being condemnatory of the American government’s inadequacies. “I Have a Dream,” didn't let the United States off the hook either, it was remarkably clear in its evaluation, but when King shared his dream with those at the National Mall it overshadowed the veracity of his criticisms. It became (and has become) easier to focus on aspiration instead of reality. Firmly rooted in reality, “Beyond Vietnam” is perhaps King's best speech, but because of what he shared at Riverside Church the last year of his life was made exceedingly more strenuous.

The Poor People’s Campaign officially launched in December 1967. King traveled to Memphis in March 1968 to assist black sanitation workers on strike. His trip to Tennessee was not organized by SCLC and a demonstration in which he participated turned violent. Determined to have a nonviolent protest, King and SCLC returned to Memphis in April. It was there he delivered his last public speech “I’ve Been to the Mountain Top” on 3 April 1968 at the Mason Temple. Less than 24 hours after King addressed those in Memphis he was murdered.

King was arguably the most gifted orator of the twentieth century — certainly in an American context — his writings, sermons, and speeches are extensive and widely available. His positions are deeply rooted in philosophical and theological traditions which he blends with distinct clarity, but they've been left in the hands of a country that created the necessity for his work, and who during his life actively stoked flames which led to his assassination.

When America was left to create King’s legacy, they decided what was relevant. Teaching American children about King’s belief in collective power wasn’t relevant. Neither boycotting corporations, nor challenging imperialism, nor forcing white America to investigate their hate, prejudice, and contempt for black people. What was relevant was keeping the revolutionary aspects of King’s philosophy in the background, magnifying the idyllic, and using nonviolence to shame any manifestation of violent dissent against the American social construct. As such, the educational system has been successful in keeping the nation stuck in 1963; it seems to understand the consequences of removing the sanitized, white-washed version of King from the national conscious and replacing him with a more accurate representation are too great. It’s easy pressing play on “Our Friend Martin,” instead of having the tough conversations about why in 1968 his public disapproval rating was almost 75 percent.

The rehabilitation campaign has been such a resounding success there is hardly any space to discuss the morally reprehensible aspects of King. A Baptist minister smoking cigarettes on the low end, to infidelity in his marriage on the high end. He was human with flaws and contradictions, but in the process of defying him, America has brushed his unsavoury aspects under the carpet, making of him an avatar to project whatever they like.

King cannot be told without “I Have a Dream.” It was a brilliant display of his humanity and unwavering faith in the humanity of others, but that speech is not the destination, it's a landmark en route to the destination. If from the Lincoln Memorial's steps one teleports to the Lorraine Motel balcony the real King is missed; and if missed ultimately King was killed for his legacy and analysis to be twisted and co-opted by the same institutions he struggled to change.